In Depth: In China, Hydrogen’s Star Rises

By You Xiaoying, Lu Yutong and Guo Jiying

In the quest for cleaner energy sources, hydrogen’s star is rising.

China is just one of a growing number of jurisdictions where policymaker and investor interest in the flammable gas is heating up. Once tarnished by its association with the fiery Hindenburg blimp disaster that punctured the hubris of Nazi Germany, hydrogen has undergone something of a revival in recent years as a promising fuel for cells that power trucks, buses and even passenger cars. The advantage over their fossil-fuel-powered counterparts is distinct: they produce no tailpipe exhaust.

Amid efforts to head off the most disastrous impacts of climate change, zero-emission cars may sound too good to be true. They are. Most hydrogen is in fact produced from fossil fuels using processes that belch out climate-warming carbon emissions, shifting the car’s pollution further upstream.

Growing political and regulatory attention on the supply chains behind green technologies could be set to change that. It’s stoked a push to develop sources of so-called low-emission hydrogen, known variously as “green” or “clean” hydrogen depending on how it is made.

In the U.S., the Biden Administration’s Inflation Reduction Act provides tax credits while the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law offers $9.5 billion in funding to spur the manufacturing of “clean hydrogen.”

The European Commission, the executive arm of the European Union, launched a long-term hydrogen roadmap in July 2020. Billions of euros in support, mostly in the form of public-private partnerships, have followed.

China launched its first long-term plan for hydrogen last year, setting clear targets for the development of “green hydrogen” by 2025, and seeking to grow its role in the nation’s energy mix significantly through 2035.

“The United States and the European Union lead policy action, while China has taken the lead in deployment,” the International Energy Agency (IEA) said.

In 2020, China accounted for less than 10% of global electrolyzer capacity installed for dedicated hydrogen production, according to the IEA in a September report. In 2022, installed capacity in China grew to more than 200 megawatts (MW), representing 30% of global capacity. By the end of 2023, China’s installed electrolyser capacity is expected to reach 1.2 gigawatts (GW), which is half of global capacity, the report said.

The Sinopec Xinjiang Kuqa Green Hydrogen Pilot Project entered full operation on Aug. 30, in a significant development for the industrial-scale implementation of green hydrogen in China. In the lower-stream transport sector, the sales of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles in China reached 4,000 in the first 11 months of this year, up 57% year on year, according to latest data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers.

In their respective pursuit of hydrogen energy, China, the U.S. and Europe have different advantages, a Caixin review of their policies shows. Europe has the most advanced policy framework. The U.S. is making inroads through generous subsidies, and its abundant natural gas resources have propelled so-called blue hydrogen projects, using technologies such as carbon capture and storage intended to reduce the fossil fuel’s carbon footprint.

Meanwhile, China’s abundant wind and solar power capacity lays a foundation for the production of green hydrogen. The nation also benefits from the low manufacturing cost of hydrogen production equipment there. Nevertheless, ensuring green hydrogen makes economic sense will be an uphill battle for all involved, insiders and experts told Caixin. The sector will need to control high costs to stoke market demand, while weathering greenwashing efforts by producers of cheaper, dirtier products.

Fuel cells to renewable hydrogen

A hydrogen cell produces only clean water and heat. Hydrogen gas, the universe’s most abundant element, dodges some of the messy supply chain issues that drag the lithium-ion electric vehicle (EV) battery sector. Hydrogen cells do require rare earth metals but do not need lithium, which is expensive and notoriously energy-intensive and environmentally-destructive to mine and refine.

Hydrogen production is a messy process too, though. China is by all accounts the world’s largest producer, generating around 33 million tons each year, according to official statistics. It does so mostly through the polluting process of coal gasification, as well as from gas, with only a sliver coming from green sources. Currently, around 90% of the hydrogen produced globally is gray hydrogen, which refers to the hydrogen produced from fossil fuels such as coal, gas and oil as well as industrial by-products, with carbon emissions during the process.

China is also the world’s largest hydrogen consumer, using more than 30 million tons annually, according to Guosen Securities Co. Ltd. in a 2021 analysis. The figure is expected to eclipse 100 million tons in the mid-to-long-term, the analysis says.

About 70% is used to make chemical compounds such as the crucial fertilizer input ammonia, rather than as an energy source, wrote Wu Mengyao, a researcher at the China Energy Media Research Institute, in a May paper.

Teng Yong, a partner at management consultancy Kearney, told Caixin that the short-term vision for hydrogen in China is to use green hydrogen to meet existing demand for gray hydrogen. In the medium term, hydrogen will be more widely used in fuel cell vehicles, as a chemical input in the production of steel, and to cut natural gas for a lower-emission blend. In the long term, he expects hydrogen will be used as a way to store energy and help power grids resolve demand bottlenecks.

Backed by strong policy support and massive local supply chains, China’s hydrogen energy industry traditionally heavily focused on fuel cells, which generate electricity through an electrochemical reaction between hydrogen and an oxidizing agent. The most popular application in China has been in trucks and buses, but they can be used to power a range of machines.

The likes of Toyota Motor Corp., BMW AG and China’s Chongqing Chang’an Automobile Co. Ltd. (000625.SZ -3.44%) have all in recent years launched hydrogen-powered passenger cars — known simply as “fuel cell vehicles” (FCV) — to muted consumer interest.

China has been subsidizing the purchase of FCVs — included in the official definition of “new energy vehicles” — since 2009, with government procurement and subsidies giving a major boost to the domestic hydrogen energy industry. As of April 2022, more than 60% of investments in hydrogen energy in China were related to fuel cells, according to Zero2IPO Research.

However, the capital market’s enthusiasm has dimmed since the second half of 2022, due to a variety of factors including delayed government payments and industry leaders’ lackluster IPOs. The country’s mid-to-long-term hydrogen plan, published in March last year, gave new impetus to the industry. Alongside an official nod to the importance of hydrogen in the nation’s energy transition, it also set a modest target: China intends to produce 100,000-200,000 tons of green hydrogen yearly by 2025. For investors, that indicates a new hydrogen opportunity other than fuel cells.

“The plan meant that there are investment opportunities based on the production end of [the hydrogen energy industry],” Luo Xiaomeng, an investor focusing on renewable energy at venture capital firm K2VC, told Caixin.

Green rush

Green hydrogen, using electricity derived from green sources, such as solar and wind, results in green hydrogen, is the gold standard. Meanwhile, “clean hydrogen” often includes another color, “blue hydrogen,” produced from fossil fuels such as gas and coal using pollution control methods that still generate significant emissions.

Green hydrogen is seen as key to slashing the global greenhouse gas emissions of energy-intensive heavy industries, such as steel and chemical manufacturing, given its potential to power industrial processes.

Less than 1% of China’s immense hydrogen production capacity is green, according to a May report released by Chinese industry consultancy TrendBank. Globally, the percentage of green hydrogen in overall hydrogen output was also about 1% in 2021, according to the International Renewable Energy Agency.

The key to boost green hydrogen is to reduce the high cost. Some say costs can be squeezed down on the production end. K2VC’s Luo said about 50-60% of the cost of hydrogen energy is incurred in production while 30% is in transport and logistics, with the rest in infrastructure.

Driven by government policy, investments in the hydrogen energy sector have shifted from hydrogen fuel cells to upper-stream production since the second half of 2022. Companies along China’s hydrogen energy industry chain announced at least 36 financing deals between January and Nov. 2, according to Gaogong Industrial Research Institute. Many involved developing hydrogen production through electrolysis.

Li Liangjun, chief expert at Sinopec Yanshan Petrochemical Co., said: “The plan, together with the supportive policies released by various local governments, has spurred the development of the upper stream of hydrogen production, especially the electrolyzer sector.”

Because hydrogen energy is infrastructure intensive, state-owned enterprises have become the spearheads of the development of the hydrogen energy industry in the context of China’s dual carbon goals.

Several large projects have made headlines in recent months. In late June, a plant capable of producing 10,000 tons of hydrogen per year using solar power came online at the site of a former coal mine in the Jungar Banner of Ordos, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. It was operated by China Three Gorges Renewables Group Co. Ltd. (600905.SH -0.22%).

Two months later, an even bigger green hydrogen plant, the Sinopec Xinjiang Kuqa Green Hydrogen Pilot Project, began production in Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region, run by China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (600028.SH -0.56%), the state fossil fuels giant better known as Sinopec.

According to Sinopec, the Kuqa plant is the largest solar-to-hydrogen project in China and is expected to produce 20,000 tons of green hydrogen every year. The hydrogen it produces will be used in the oil refining process of Sinopec’s nearby chemical factory, in place of the gas-produced hydrogen the factory currently uses, according to the firm.

The company is building another mega green hydrogen factory in Ordos, which will use solar and wind power to make 30,000 tons of hydrogen every year.

In Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Guohua Investment Management Corp., Ltd., a subsidiary of CHN Energy Investment Group Co. Ltd., is in the final stages of constructing a green hydrogen factory, also using solar power. It is part of a “renewable hydrogen demonstration project” that includes a fuel station able to service 150 heavy FCV trucks daily, Guohua said in September.

The ability to transport green hydrogen from the renewables-abundant west China to the energy-hungry east will be crucial to meeting the goals of China’s hydrogen roadmap, Jin Boyang, senior energy transition analyst at data provider Refinitiv, told Caixin in September.

It will be easier said than done. Hydrogen’s chemical nature — a simple, highly reactive structure and low density — adds logistical and maintenance costs. It easily escapes containment, wears on machines, and requires special tanks and infrastructure to store and transport. Its flammability, if mixed with even a tiny amount of air, adds complexity and danger.

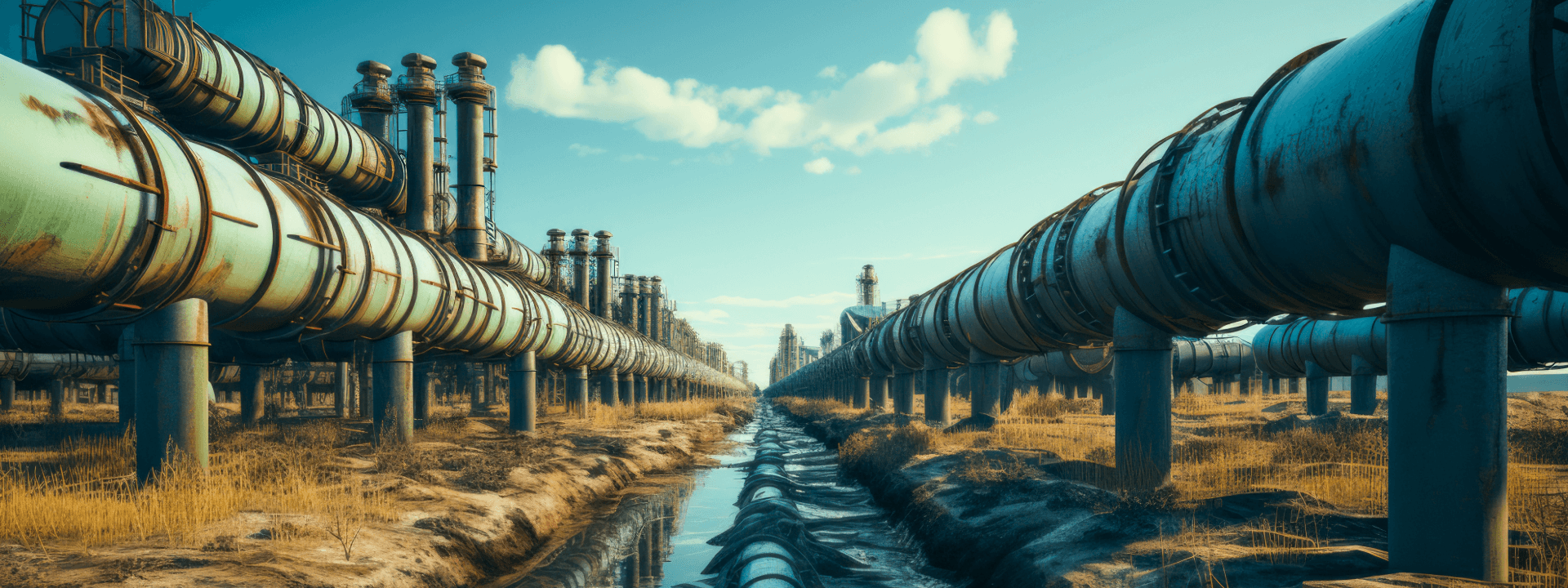

Sinopec is developing a network of pipes as part of its “west-to-east hydrogen transporting program,” Sinopec Yanshan Petrochemical’s Li told Caixin.

The first phase of the program will start in Ulanqab in Inner Mongolia and will terminate more than 400 kilometers (248.5 miles) away in Beijing, according to a Sinopec press release in April. It is the first cross-provincial and long-distance network of pipes exclusively for transporting hydrogen, it said.

Electrolyzer undersupply emerges

The rise of green hydrogen projects has also revved up interest in underlying technologies.

In the first six months of this year, Chinese electrolyzer manufacturers have won contracts for 815 MW worth of electrolyzers, already surpassing 2022’s output, according to analysts at Guosen Securities Co. Ltd. in a July report. These electrolyzer-makers are expected to ship 2.3 GW of products this year, according to the report.

Meanwhile some 200 companies are planning to expand their business to alkaline electrolyzers, including firms in both the fossil fuels and renewables sectors, according to TrendBank in an August report. Alkaline electrolyzers are the main type of electrolyzers manufactured in China.

But as the market booms, electrolyzer companies face a cut-throat price war and are struggling to deliver bulk orders on time, a person from a Beijing-based hydrogen and fuel cell industry group told Caixin. He said that in order to win bids, some companies have quoted prices lower than their production cost for alkaline electrolyzers, creating “vicious competition” in the industry.

He added that only 30 or 40 electrolyzer manufacturers in China have experience producing bulk orders, while the rest have yet to start making goods at scale. He predicted “very few” firms will be able to deliver on their contracts on time.

High overheads

Making green hydrogen in China is estimated to cost between 33.9 yuan ($4.72) and 42.9 yuan per kilogram, according to a report released by the World Economic Forum in June. On average, the figures are at least three times the costs of coal-produced hydrogen and “considerably more” than hydrogen produced from gas or as an industrial by-product, the report said.

Some industry insiders say that ultimately, government intervention may prove the only way to make green hydrogen a viable choice and drive large-scale adoption. Market demand is curbed by the high costs of the gas. That means either the per unit cost must be driven down, or the cost-penalty of using dirty alternatives will need to rise.

Sinopec Yanshan Petrochemical’s Li highlighted that wear and tear on machines such as electrolyzers pushes up production costs. And since green hydrogen is made using renewable energy that tends to be intermittent, the maintenance of machines that need to start and stop often adds further costs.

Even flagship projects will likely struggle to stay afloat financially. Citing the recently commissioned Kuqu mega green hydrogen plant as an example, the person from the hydrogen industry group said that even though the project carries great significance, it is “not really economically viable.”

Expanding China’s emissions trading system to manufacturing and heavy industry could be a feasible way to lift demand for green hydrogen, according to multiple industry insiders.

Gao Xitong, a hydrogen analyst at BloombergNEF, told Caixin that the energy transition comes hand in hand with increases in energy costs. “If China insists on keeping the costs of energy low, then it would be hard [for it] to make the first step in low-carbon development,” Gao said.

China’s national emissions trading system only includes the power-generation sector, though there have been talks about it being expanded to other industrial sectors, such as steel, petrochemicals and building materials.

China’s national carbon price was averaged at less than $10 per ton in 2022, according to calculations by Jenny Yang and Megan Jenkins, analysts at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

But to level the playing field between companies using green hydrogen in their production and those using dirtier sources, the carbon price would need to increase tenfold to more than $86 per ton, according to Yang and Jenkins.

One source of fat to be trimmed could be found in the cost of energy inputs. They currently account for as much as half of production costs, insiders say. That means lowering the cost of renewable energy, and developing new technology to produce green hydrogen in a cheaper and more efficient way, according to Fang Wei, a vice president at Sungrow Power Supply Co. Ltd. (300274,SZ +0.53%)’s hydrogen department.

Fang told Caixin that China’s hydrogen energy industry is still in an early stage, and therefore technological research and innovation is needed. “If [we] view hydrogen as a future energy, then we shouldn’t rush it,” he said.

Read also the original story.

caixinglobal.com is the English-language online news portal of Chinese financial and business news media group Caixin. Global Neighbours is authorized to reprint this article.

Image: senadesign – stock.adobe.com