Weekend Long Read: When China Speed Meets Brazil Rhythm

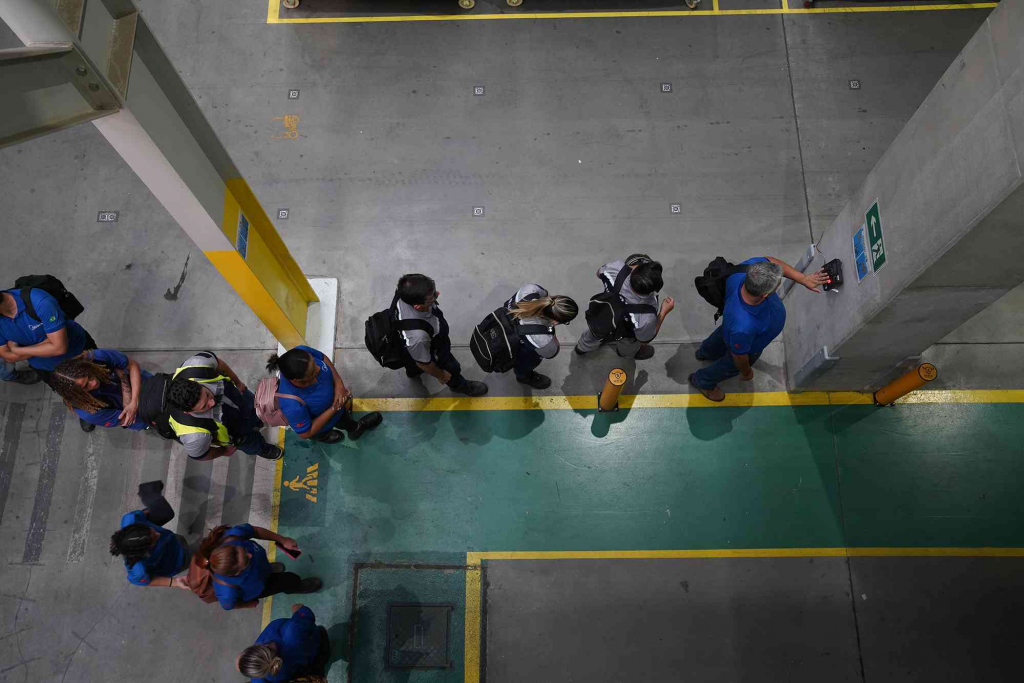

At 4:10 p.m., just 20 minutes before the official end of the workday, the production line at a Chinese-owned factory in Brazil has already fallen quiet. Workers have packed their bags, and a long line snakes toward the time clock.

It is a far cry from the grueling schedules common in China. Here, the factory runs a 44-hour workweek with weekends off, and employees even leave an hour early on Fridays. At 4:30 p.m. sharp, a stream of workers boards company buses that ferry them home, some to neighboring cities as far as 80 kilometers (49.7 miles) away.

The relaxed pace reflects a recent all-staff vote to move the workday forward by two hours, giving employees time to hit the gym, shop for groceries or visit a bank before everything closes.

For Chinese managers accustomed to a top-down approach, the change amounts to more than a tweak to the clock. It is a lesson in a different way of doing business. As Chinese investment deepens across Latin America, companies are learning that their vaunted “China speed” — a culture of high velocity and high pressure — must contend with strict labor laws and deeply ingrained norms in places such as Brazil.

As they push deeper into local markets, Chinese entrepreneurs are navigating a workplace culture where overtime is subject to a vote, holidays are plentiful, and a manager who raises his voice can trigger an expensive lawsuit. The collision is forcing executives to recalibrate, offering Brazilian workers the stability of strong protections while exposing them to the sometimes jarring but instructive discipline of a results-driven corporate ethos.

Balance act

“My temper has gotten much better,” said Wang Haijun, a Chinese manager who has run the factory for nearly a year. As the buses pull away, Wang turns back to his office to continue working.

“In China, it’s normal for employees to be criticized when they don’t perform well,” he said. “But here, if you raise your voice even slightly, the other person may think you’re discriminating against them or treating them unfairly.” Communicating calmly — and cautiously — is essential.

Wang described the local preference as one for “happy education,” adding that Brazilian employees can be more psychologically sensitive than Chinese managers expect. “When I first arrived, I wasn’t used to it,” he recalled. “I would speak a little too harshly, and tears would immediately well up in their eyes.”

To foster encouragement, Wang began posting photos of outstanding employees in the hallways and holding year-end raffles with prizes such as refrigerators and smartphones.

The careful approach extends well beyond interpersonal relations. Arranging a weekend shift to meet an urgent order requires running a bureaucratic gauntlet. Management must submit a request at least two weeks in advance, first to the labor union and then to workers for a vote. If more than half agree, overtime can proceed — though attendance remains voluntary.

Brazil’s legal landscape is a constant source of anxiety. Labor courts tend to favor workers, who can easily obtain free legal support. Wang’s factory strictly follows mandates on equal pay for equal work, meaning even cash bonuses can spark complaints. Violations can result in hefty payouts.

One Chinese-owned company learned the lesson the hard way. An employee, in his final month before resigning, emailed his supervisor about work every night after 8 p.m. The manager replied promptly, pleased by the diligence. The employee later compiled the emails as evidence of unpaid overtime and sued, seeking more than 1 million yuan ($142,000). Some firms now shut down email systems from 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. as a preventive step.

Lan Fengqiang, a public relations manager at state-owned automaker Great Wall Motor Co. Ltd.’s Brazil factory, said labor law even dictates office ergonomics, requiring mouse pads with wrist guards and footrests for shorter employees. Pandemic-era habits have endured: the company operates on a hybrid schedule, with three days in the office and two at home. Wang’s firm employs a legal team to build a compliance framework and outsources restroom and cafeteria maintenance, since poor sanitation can be deemed a serious violation. Even the factory’s design was altered to meet local rules.

The costs are steep. Wang estimated operating expenses are one and half to two times greater than those in China. While base pay may be lower, benefits are far richer, including mandatory health insurance, two free meals a day, transportation and afternoon tea. With numerous holidays, annual working days total fewer than 240. “If an employee has a family of three, the company pays more than 600 reais ($110) a month just for insurance,” Wang said.

Each year brings another test: mandatory wage negotiations with unions, which must at least keep pace with inflation.

China-Brazil fusion

When a Brazilian woman we’re calling Maria interviewed with Chinese logistics giant J&T Express Co. Ltd. in northern Brazil, the company lacked even an office. She met a Chinese executive and a translator in a shopping mall cafe. “We will strive to be number one in Brazil,” the executive told her.

Skeptical but eager for a breakthrough, Maria joined anyway. Now the company’s northern operations manager, she said four years at J&T equaled a decade elsewhere. “The pressure makes you grow,” she said.

Traditional Brazilian firms prefer exhaustive planning before acting. At her previous job, replacing an operating system took a year. At J&T, the credo is act first, correct later. The company switched systems immediately, enduring two months of problems before stabilizing.

“That urgency teaches a lifelong skill,” Maria said. “You test, fail fast, then revise.”

A Brazilian man we’ll calling Raymond, another senior local employee at J&T Brazil, said adapting to the results-driven mindset took time. Chinese managers want details, he said, and sometimes propose ideas that seem bizarre locally — such as delivering parcels on foot in sprawling neighborhoods.

Yet some gambles paid off. When a manager insisted on opening a large hub in Belém despite low volumes, Raymond’s team objected. The hub now handles thousands of orders a day. “We found trust through conflict,” Raymond said.

The fusion is reshaping competition. Traditional logistics firms build wide buffers, taking eight to 12 days for deliveries that J&T now completes in one or two. The company even broke with the tradition of closing on Sundays, forcing complex shift schedules.

“We had to meet the board’s goals and still find solutions Brazilian employees could accept,” Raymond said. “This is neither a purely Brazilian rhythm nor a Chinese one. It’s a new model.”

Remaking the professional landscape

The influence of Chinese companies reaches beyond factories. At the Confucius Institute in Belém, a local lawyer we’ll call Bruno, practices Chinese. Professionals now make up more than 40% of enrollment in classes at the institute.

“Beyond language, they value the platform and the connections,” said Sun Jing, the institute’s Chinese director. Through the network, Bruno now consults for several Chinese firms.

The influx of Chinese ride-hailing and delivery apps has also created new business models and reshaped livelihoods. A single mother we’re calling Natasha found independence as a courier for 99, owned by Didi Global. After years of low-paid work and a stint as an emergency-room nurse during the pandemic, she quit to work for 99 full time.

On her first day, she earned 250 reais — about a week’s hospital pay. The income helped her build a house and raise her daughter. Now she works mornings, spends afternoons with her child, and recently earned a motorcycle repair certificate with a perfect score.

She posts videos encouraging other women to join. “Be brave,” she said. “Don’t depend on others. If you have a motorcycle and can ride, go for it.”

Contact editor Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com)

caixinglobal.com is the English-language online news portal of Chinese financial and business news media group Caixin. Global Neighbours is authorized to reprint this article.

Image: Amin Rajput – stock.adobe.com