AI Hiring Thaw Helps Relieve Tech Talent Glut in China

By Ma Shiwen and Tang Hanyu

Li Haoran, who did not major in computer science, spent the better part of his final year in university cycling through internships and job applications. After failing to secure a satisfactory offer during the main autumn recruitment season in 2024, he kept interning and interviewing until May, finally landing a position in the large-model division of a major Chinese tech company.

In Li’s view, his persistence paid off thanks to a hiring surge in the first half of 2025. The rise of new players like DeepSeek spurred China’s tech giants to ramp up their artificial intelligence (AI) operations, creating a fresh wave of opportunities.

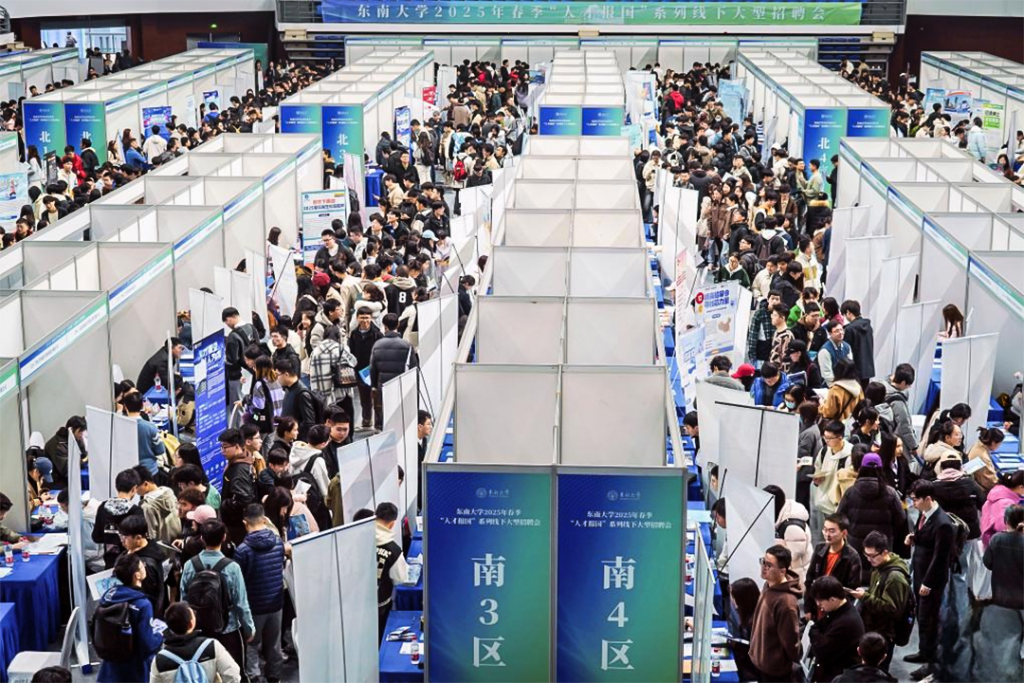

His experience, along with a recent flurry of ambitious campus recruitment announcements from China’s internet titans, suggests a potential thaw after several “cold winters” that have chilled the industry since the pandemic began, but for the hundreds of thousands of computer science students graduating into this market, the reality is far more complex.

While some see signs of a spring rebound, particularly in the booming field of AI, broader data and the experiences of many others paint a picture of a shrinking market where competition has become a grueling, multi-year marathon. The path to a coveted job at one of China’s “big factories,” as the tech behemoths are known, is now paved with intensifying demands for elite academic credentials and extensive internship experience, leaving many graduates squeezed out of a field once seen as a golden ticket.

A tentative thaw

This year, several of China’s largest tech companies have released recruitment plans that, on the surface, send a friendly signal to anxious job seekers.

Tencent Holdings Ltd. in April unveiled what it called its “largest ever employment plan,” promising to add 28,000 internship positions over three years and increase the rate at which interns are converted to full-time employees. For 2025 alone, the company plans to bring in 10,000 campus-recruited interns, with 60% of the roles designated for technology talent. It also launched the “Qingyun Plan,” a special recruitment drive to attract top global technology students for its large-model division, which it identified as a key area of investment.

Baidu Inc. announced it would open 21,000 internship positions over the next three years. In March, it had already opened over 3,000 summer internship roles, with 87% related to AI in fields like large models, machine learning, and autonomous driving.

JD.com Inc. said it would employ its “largest ever retention effort” for its intern program starting this year, offering more than 10,000 internship positions with the potential for full-time conversion in 2025. In late July, the e-commerce giant got a head start on the next cycle, launching its 2026 campus recruitment 11 days earlier than last year. The new plan includes 35,000 openings — 20,000 for recent graduates and 15,000 for interns.

This flurry of activity has fueled a sense of optimism among some students, a stark contrast to the gloom of recent years.

“This year is a time of peace and prosperity at the big factories; the employment situation is better than the past three years,” said one undergraduate computer science major from a prestigious university in central China, who is set to begin his doctoral studies. He and his peers choosing further education, however, worry that the job offers they receive after graduate school might not match what this year’s bachelor’s degree holders are securing.

Chen Chen, also a graduate of a top university’s computer science program, said his cohort has “received more opportunities” than the class before them, many of whom were still searching for jobs during the spring recruitment window. This year, many of his classmates were able to finalize their employment during the main autumn recruitment drive.

A market reshaped

This hyper-competitive environment for graduates is playing out against a backdrop of a broader structural shift in the industry’s labor market. A look at financial reports from China’s tech giants reveals a clear inflection point around 2022, when years of double-digit employee growth reversed into decline.

Baidu and Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. have seen their headcounts fall for three consecutive years. At the end of 2024, Baidu’s workforce stood at 35,900, down 21.1% from its 2021 peak. Its research and development (R&D) staff fell 29% over the same period. Alibaba’s full-time employee count plummeted by over 50%, from 254,941 on March 31, 2022, to 124,320 on March 31, 2025. The company attributed much of the 2025 fiscal year decrease to deconsolidating Sun Art Retail Group after its sale.

Even at JD.com, where the overall workforce has grown to over 570,000, the number of technology-related positions has fallen nearly 15% from a peak of 17,000 in 2021 to 15,000.

“The huge tailwind from the mobile internet boom between 2010 and 2015 is gone,” said Yan Yan, a development engineer with nearly five years of experience who has interviewed candidates at three major tech companies.

While new trends like AI create some jobs, she said, tech companies are tightening their salary budgets. “It used to be that you could easily get a 50% or even 100% salary increase by switching jobs. Now, everyone is capping it at 30%. This is a reduction of capital market money.”

On the other side of the equation, the supply of talent is swelling. Chinese universities have continued to expand enrollment in computer science. According to a report from education data provider Eol.cn, national enrollment plans for computer science-related majors totaled about 435,000 in 2024, an increase of over 40,000 from the previous year.

This expansion has led to warnings of a supply glut. According to a tally by education evaluation agency Shanghai Ranking, computer science and technology was one of the most frequently red-flagged majors across nine provinces, signaling that it is either over-enrolled or has a low employment rate.

“The supply of people who might have gone to small and medium-sized companies because their academic credentials weren’t as high are now unable to find jobs,” Yan said. “This part of the supply, like the bottom layer of a pyramid, is being shaved off.”

The consequences are visible in employment data. A 2025 Blue Book on employment from MyCos Research showed that the employment placement rate for 2024 computer science undergraduates six months after graduation was just 82.4%, significantly below the national average of 86.7% and a drop from the 86.6% rate for the class of 2022. While their average monthly salary of 6,846 yuan ($945) was above average, it was slightly below the 6,863 yuan earned by their 2022 predecessors.

The industry, the report concluded, is facing cyclical adjustments and talent oversupply, while emerging roles in AI and big data demand higher academic qualifications, putting downward pressure on salaries for bachelor’s degree holders. For China’s aspiring coders, the message is clear: the gold rush is over, and an era of intense, painstaking competition has begun.

All students and Yan Yan are identified by pseudonyms.

Ma Shiwen is an intern at Caixin Media.

Contact editor Lu Zhenhua (zhenhualu@caixin.com)

caixinglobal.com is the English-language online news portal of Chinese financial and business news media group Caixin. Global Neighbours is authorized to reprint this article.

Image: Sutthithong – stock.adobe.com